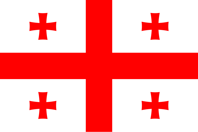

SPEAK GEOrGIAN FLUENTLY

IT’S TIME TO

MASTER GEORGIAN GRAMMAR

Despite what you have heard, Georgian grammar is actually quite easy to learn! This Grammar Section is designed to make learning the rules as quick as possible so you can start building your own sentences. Unlike other courses we want you to familiarise with the most important rules to speak Georgian immediately from today.

We use the Zagreb Method for teaching grammar. Instead of presenting grammar as abstract rules, we integrates it directly into real-life communication and scenarios. Our students are introduced to grammar through dialogues and situational context that reflect everyday interactions. The method also incorporates repetition and variation, gradually increasing the complexity of sentences to help learners internalize grammatical patterns naturally.

The sections below cover everything you need to know from basic sentence construction and verb conjugations to more complex topics like noun cases, gender agreements, together with practical examples to help you understand and memorise the Georgian grammar rules. Be sure to learn the core 2000 Georgian vocabulary first so you can follow the examples more easily.

Click on the titles below to reach the section you are interested in or simply start learning from the beginning.

Georgian Alphabet

The Georgian Alphabet and Pronunciation

The Georgian alphabet, known as Mkhedruli (მხედრული mkhedruli), is one of the most unique and visually distinctive writing systems in the world. Unlike most other scripts, it is not derived from Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, or Arabic but is instead an entirely independent script. It consists of 33 letters, all of which are written in the same case (there is no distinction between uppercase and lowercase). The alphabet has evolved over centuries, originating from the earlier Asomtavruli (ასომთავრული asomtavruli) and Nuskhuri (ნუსხური nuskhuri) scripts, which are still used in religious contexts today.

Georgian is a phonetic language, meaning that words are generally pronounced as they are spelled, with very few exceptions. Each letter corresponds to a specific sound, making the pronunciation relatively straightforward once the script is mastered. However, Georgian has unique phonetic features, including complex consonant clusters and sounds that are unfamiliar to speakers of many other languages.

Structure and Features of the Georgian Alphabet

The Mkhedruli script consists of 33 letters, each representing a single phoneme (sound). Unlike some languages, Georgian does not use additional diacritics or accents. Every letter has a distinct shape, and the script is written from left to right.

One of the defining characteristics of the Georgian alphabet is its rounded and flowing appearance. The letters do not have sharp angles or straight lines like some other scripts, which contributes to its unique aesthetic.

Another important feature is that each letter has a fixed pronunciation, with no variation based on surrounding letters. This makes Georgian easier to read and pronounce compared to languages with complex spelling rules.

Pronunciation in Georgian

Vowels

Georgian has five vowels:

ა (a) – pronounced like the "a" in father

ე (e) – pronounced like the "e" in bet

ი (i) – pronounced like the "ee" in see

ო (o) – pronounced like the "o" in lot

უ (u) – pronounced like the "oo" in food

These vowels are always pronounced clearly and do not change based on stress or surrounding consonants. Unlike in some languages, vowels in Georgian do not form diphthongs; each vowel is pronounced separately, even if two vowels appear next to each other.

Consonants

Georgian has 28 consonants, including some that may be challenging for non-native speakers. The language features ejective consonants, which are pronounced with a burst of air from the throat rather than the lungs. These ejective sounds are marked with an apostrophe in transliteration.

Common Consonant Sounds

ბ (b) – like the "b" in boy

გ (g) – like the "g" in go

დ (d) – like the "d" in dog

ვ (v) – like the "v" in victory

ზ (z) – like the "z" in zebra

თ (t) – like the "t" in top

კ (k) – like the "k" in sky (unaspirated)

პ (p) – like the "p" in spy (unaspirated)

ტ (t) – like the "t" in stop (unaspirated)

ფ (pʰ) – like the "p" in pen (aspirated)

ხ (kh) – like the "ch" in Bach (a strong "h" sound)

Ejective Consonants

Ejective consonants are pronounced with a burst of air from the throat:

ქ (k’) – a hard "k" sound

წ (ts’) – a hard "ts" sound

ჭ (ch’) – a hard "ch" sound

ფ (p’) – a hard "p" sound

For example, the word წიგნი (ts’igni) book contains the ejective consonant წ (ts’), which is pronounced with a sharp burst of air.

Complex Consonant Clusters

One of the most challenging aspects of Georgian pronunciation is its consonant clusters. Unlike many languages that alternate between vowels and consonants, Georgian allows multiple consonants to appear together without vowels in between.

For example:

მთვარე (mtvare) moon – starts with მთვ (mtv)

ცხელი (tskheli) hot – starts with ცხ (tsk)

გთხოვ (gtkhov) please – starts with გთხ (gtkh)

These clusters can be difficult for learners, but mastering them is essential for fluency.

Word Stress in Georgian

Georgian does not have strong stress patterns like English or Russian. The primary stress usually falls on the first syllable, but it is weak compared to many other languages. This makes Georgian pronunciation even and smooth, with no dramatic rises or falls in intonation.

For example:

საქართველო (sakartvelo) Georgia – stress is on სა (sa)

თბილისი (tbilisi) Tbilisi – stress is on თბ (tbi)

მასწავლებელი (masts’avlebeli) teacher – stress is on მას (mas)

Because stress is weak, it is important to pronounce every vowel clearly, as vowel reduction does not occur in Georgian.

The Georgian language has a unique and complex grammatical structure, and its nouns function differently from those in many Indo-European languages. Unlike English, Georgian nouns do not have grammatical gender, and they do not change based on definiteness (there are no articles like a or the). Instead, nouns are modified by suffixes, prefixes, and postpositions to indicate relationships, meaning, and function within a sentence.

Noun Structure in Georgian

Georgian nouns consist of a root to which various suffixes may be added. Unlike in many other languages, Georgian does not have grammatical gender distinctions such as masculine, feminine, or neuter. This means that words like ბიჭი (bichi) boy and გოგო (gogo) girl do not have different endings or changes based on gender.

Some Georgian nouns change form based on number, possession, and role in the sentence, but the base noun remains unchanged in most contexts.

Number: Singular and Plural

Georgian nouns can be either singular or plural, with pluralization typically achieved by adding a suffix. The most common plural suffixes are -ები (-ebi) and -ნი (-ni), but other variations exist depending on the word.

Examples of Singular and Plural Forms

სახლი (sakhli) house → სახლები (sakhlebi) houses

ფანჯარა (panjara) window → ფანჯრები (panjrebi) windows

ბავშვი (bavshvi) child → ბავშვები (bavshvebi) children

წიგნი (tsigni) book → წიგნები (tsignebi) books

The -ები (-ebi) suffix is the most common and applies to many nouns. However, some words take -ნი (-ni) instead, though these are less frequent.

Some nouns have irregular plurals where the base form changes slightly:

კაცი (k’atsi) man → კაცები (k’atsebi) men

ცხვარი (tskvari) sheep → ცხვრები (tskvrebi) sheep (plural)

ხე (khe) tree → ხეები (kheebi) trees

Definiteness and Indefiniteness

Unlike English, Georgian does not have articles such as a or the. The meaning of definiteness is understood from context rather than through a specific word.

For example:

მე ვხედავ სახლს (me vkhedav sakhs) I see a house / I see the house

კატა ეზოში ზის (kata ezoshi zis) A cat is sitting in the yard / The cat is sitting in the yard

The noun სახლი (sakhli) house does not change form regardless of whether it is definite or indefinite. The context determines whether the noun refers to a specific or general object.

Possession in Georgian Nouns

Possession in Georgian is expressed using possessive pronouns or possessive suffixes.

Possessive Pronouns

ჩემი (chemi) my

შენი (sheni) your (singular)

მისი (misi) his/her/its

ჩვენი (chveni) our

თქვენი (tkveni) your (plural/formal)

მათი (mati) their

Examples:

ჩემი სახლი (chemi sakhli) my house

შენი მეგობარი (sheni megobari) your friend

მისი ძაღლი (misi dzaghli) his/her dog

Instead of possessive pronouns, possessive suffixes can also be added directly to nouns:

სახლი ჩემი (sakhli chemi) house mine → ჩემი სახლი (chemi sakhli)

ბიჭის წიგნი (bichis tsigni) the boy’s book

Possession using suffixes is also commonly seen when referring to family members:

დედაჩემი (dedachemi) my mother

მამაჩემი (mamachemi) my father

და შენი (da sheni) your sister

Diminutive and Augmentative Forms

Georgian uses diminutive and augmentative suffixes to modify the size or affectionate tone of a noun. These changes do not indicate grammatical case but serve to express emotional nuance.

Diminutives (small or affectionate form of a noun)

Common diminutive suffixes: -უკა (-uka), -იკა (-ika), -უჩი (-uchi)

ბავშვი (bavshvi) child → ბავშუკა (bavshuka) little child

კატა (kata) cat → კატიკა (katika) cute little cat

ძაღლი (dzaghli) dog → ძაღუჩი (dzaghuchi) small dog

Augmentatives (larger or exaggerated form of a noun)

Some augmentative suffixes: -ანა (-ana), -ურა (-ura)

კაცი (k’atsi) man → კაცურა (k’atsura) big man

სახლი (sakhli) house → სახლურა (sakhlura) large house

Loanwords and Adaptation

Georgian has borrowed words from Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Russian, and English over the centuries. Loanwords are adapted to fit the Georgian phonetic and grammatical system. Some examples include:

ტელევიზორი (televizori) television (from English "television")

ბანკი (banki) bank (from English "bank")

ავტობუსი (avtobusi) bus (from English "autobus")

ქიმია (kimia) chemistry (from Greek "chemia")

These words are fully integrated into the Georgian language and behave like native nouns in terms of pluralization and possession.

Compound Nouns

Georgian forms compound nouns by combining two words to create a new meaning. Some examples include:

მზესუმზირა (mz’esumzira) sunflower (from მზე (mze) sun + სუმზირა (sumzira) facing)

თვალსაზრისი (tvalsazrisi) point of view (from თვალი (tvali) eye + აზრი (azri) opinion)

მუშახელო (mushakhelo) workforce (from მუშა (musha) worker + ხელი (kheli) hand)

Nouns in Georgian

Cases in Georgian

Georgian is a case-marking language, meaning that nouns change their endings depending on their function within a sentence. Cases indicate whether a noun is the subject, object, possession, location, or plays another grammatical role. There are seven grammatical cases in Georgian, each serving a different function.

Unlike in many languages, Georgian cases are marked by suffixes added to the noun. These suffixes vary depending on the structure of the word and its role in the sentence. Cases apply not only to nouns but also to adjectives, pronouns, and some numerals.

Nominative Case

The nominative case is the base form of a noun and is used for the subject of a sentence. This is the form found in dictionaries, and it does not require any suffixes.

Examples:

ბიჭი თამაშობს (bichi tamashobs) the boy is playing

ქალი მღერის (kali mgherisi) the woman is singing

თევზი ცურავს (tevzi tsuravs) the fish is swimming

In these examples, ბიჭი (bichi) boy, ქალი (kali) woman, and თევზი (tevzi) fish are all in the nominative case because they are the subjects of their respective sentences.

Ergative Case

The ergative case appears in past tense transitive verbs, meaning that in certain past-tense constructions, the subject takes a different form. It is typically formed by adding -მა (-ma) or -მა (-m) to the noun.

Examples:

ბიჭმა ნახა ფილმი (bichma nakha pilmi) the boy watched the movie

ქალმა გააკეთა ნამცხვარი (kalma gaaketa namtskvari) the woman made a cake

დედამ დაურეკა შვილს (dedam daureka shvils) the mother called the child

In these examples, ბიჭმა (bichma), ქალმა (kalma), and დედამ (dedam) are in the ergative case because they are performing an action in the past tense with a direct object.

Dative Case

The dative case is used for indirect objects, the subject of some verbs, and in some constructions in the future and past tenses. The dative suffix is -ს (-s), but some words take irregular forms.

Examples:

ბიჭს წიგნი მისცეს (bichs tsigni mistses) they gave the book to the boy

ქალს ვაშლი მოაწოდეს (kals vashli moatsodes) they handed an apple to the woman

ძაღლს ძვალი უყვარს (dzaghl dzvali uqvars) the dog loves the bone

The dative case is also used when the subject experiences something rather than actively doing it:

ბიჭს სცივა (bichs stsiva) the boy is cold

ქალს ეშინია (kals eshinia) the woman is afraid

მამას უხარია (mamas ukharia) the father is happy

In these cases, the experiencer (the person who feels something) is in the dative case rather than the nominative.

Genitive Case

The genitive case shows possession or relation. It is usually formed by adding -ის (-is) to the noun, but some nouns change their endings irregularly.

Examples:

ბიჭის წიგნი (bichis tsigni) the boy’s book

ქალის ჩანთა (kalis chanta) the woman’s bag

მამის სახლი (mamis sakhli) the father’s house

The genitive case can also indicate part of something:

ხის ფესვი (khis fesvi) the tree’s root

მთის მწვერვალი (mtis mtsvervali) the mountain’s peak

In compound phrases, only the first noun takes the genitive suffix:

ბიჭის ძაღლი (bichis dzaghli) the boy’s dog

მასწავლებლის ოთახი (masts’avleblis otakhi) the teacher’s room

Instrumental Case

The instrumental case expresses means or method. It often answers the question "with what?" and is marked with the suffix -ით (-it).

Examples:

პასტით ვწერ (pastit vts’er) I am writing with a pen

დანა გაჭრა პურით (dana gatchra purit) he cut the bread with a knife

ფუნჯით ხატავს (funjit khatavss) he is painting with a brush

The instrumental case is also used for certain adverbial expressions:

სიხარულით ველოდები (sikharulit velodebi) I am waiting with joy

სიყვარულით მივესალმები (siqvarulit mivesalmebi) I greet with love

Adverbial Case

The adverbial case describes states, transformations, or roles. It is usually marked by -დ (-d).

Examples:

ბიჭი ექიმად მუშაობს (bichi ek’imad mushaobs) the boy works as a doctor

მან მსახიობად იქცა (man msakhiobad iqtsa) he became an actor

ის გმირად აღიარეს (is gmirad aghiares) he was recognized as a hero

It is also used to indicate manner:

ბედნიერად ვგრძნობ თავს (bednierad vgrdznob tavs) I feel happy

სწრაფად გაიქცა (sts’rapad gaik’tsa) he ran quickly

Vocative Case

The vocative case is used when directly addressing someone or something. In many cases, it does not change the noun’s form, but for some words, a suffix -ო (-o) is added.

Examples:

მამაო, მოდი აქ! (mamao, modi ak!) Father, come here!

ნინო, გისმენ! (nino, gismen!) Nino, I am listening!

ბიჭო, რას აკეთებ? (bicho, ras aketeb?) Boy, what are you doing?

This form is mostly used in direct speech and often expresses emotion, urgency, or respect.

One of the most distinctive features of the Georgian language is that it does not have articles like a, an, or the in English. In many languages, articles are used to indicate whether a noun is definite (specific) or indefinite (general). However, in Georgian, definiteness and indefiniteness are understood from context rather than being explicitly marked by a separate word.

This means that a single Georgian noun can often correspond to multiple English translations depending on the situation.

For example:

სახლი დიდია (sakhli didia) the house is big / a house is big

ვხედავ მანქანას (vkhedav mankanas) I see the car / I see a car

In both cases, the noun სახლი (sakhli) house and მანქანა (mankana) car can be understood as either definite or indefinite depending on the context of the sentence.

How Does Georgian Indicate Definiteness?

Even though Georgian does not use articles, there are several ways that definiteness can be conveyed in a sentence. These include word order, demonstrative pronouns, context, and suffixes.

Context and Word Order

In many cases, whether a noun is definite or indefinite is clear from the surrounding words and the situation.

For example:

ქუჩაში ბავშვი თამაშობს (kuchashi bavshvi tamashobs) a child is playing in the street

ბავშვი ჩემი მეგობრის ვაჟია (bavshvi chemi megobris vajiia) the child is my friend’s son

In the first sentence, ბავშვი (bavshvi) child is likely indefinite because no specific child has been mentioned before. However, in the second sentence, the same word ბავშვი (bavshvi) is definite because it refers to a known child (the speaker’s friend’s son).

Similarly:

მინდა წიგნი (minda tsigni) I want a book / I want the book

მინდა ეს წიგნი (minda es tsigni) I want this book

In the first sentence, წიგნი (tsigni) book could be definite or indefinite depending on the context. If the speaker has already mentioned a specific book, it would be understood as the book. If no book has been mentioned before, it would mean a book.

Demonstrative Pronouns to Indicate Definiteness

To make a noun explicitly definite, Georgian often uses demonstrative pronouns like ეს (es) this or ის (is) that.

Examples:

ეს სახლი ლამაზია (es sakhli lamazia) this house is beautiful

ის ბიჭი ჩემი ძმაა (is bichi chemi dzmaa) that boy is my brother

ეს წიგნი ძალიან საინტერესოა (es tsigni dzalian sainteresoia) this book is very interesting

When a demonstrative pronoun is used, the noun is always definite, much like using the in English.

On the other hand, if no demonstrative pronoun is used, the noun could be either definite or indefinite:

წიგნი ძვირია (tsigni dzviria) the book is expensive / a book is expensive

ეს წიგნი ძვირია (es tsigni dzviria) this book is expensive (explicitly definite)

Using Personal Pronouns for Definiteness

Sometimes, definiteness can also be indicated by using possessive pronouns, which explicitly specify ownership.

Examples:

ჩემი მანქანა ახალია (chemi mankana akhalia) my car is new

მისი სახლი დიდია (misi sakhli didia) his/her house is big

Since the noun is possessed by someone, it is always definite, just like in English (the car that belongs to me).

How Does Georgian Express Indefiniteness?

Just as Georgian does not have a definite article (the), it also does not have an indefinite article (a, an). Instead, indefiniteness is usually inferred from context, or it can be emphasized using words that indicate uncertainty or generality.

Using Context to Express Indefiniteness

In most cases, when a noun is first introduced into a conversation, it is understood as indefinite.

Examples:

ქუჩაში კაცი დავინახე (kuchashi k’atsi davinakh) I saw a man in the street

ბაღში ყვავილი იზრდება (baghshi qvavili izrdeba) a flower is growing in the garden

In these examples, the nouns კაცი (k’atsi) man and ყვავილი (qvavili) flower are understood as new, unspecified information, meaning that they are indefinite.

However, if the same noun is mentioned again in the conversation, it may become definite:

ქუჩაში კაცი დავინახე. კაცმა ჩემთან გამოიქცა. (kuchashi k’atsi davinakh. katsma chemtan gamoik’tsa.) I saw a man in the street. The man ran toward me.

Here, კაცი (k’atsi) man is indefinite in the first sentence but becomes definite in the second because the speaker and listener now know which man is being discussed.

Using "ერთი" (erti) for Indefiniteness

The word ერთი (erti) one is sometimes used similarly to the English "a" or "an" when introducing a new, unspecified noun.

Examples:

ერთი ბიჭი მელაპარაკა (erti bichi melaparaka) a boy talked to me

ერთი წიგნი ვიყიდე (erti tsigni vqide) I bought a book

However, ერთი (erti) is not always necessary. In many cases, nouns can still be understood as indefinite even without it.

Compare:

ბიჭი მოვიდა (bichi movida) a boy arrived / the boy arrived

ერთი ბიჭი მოვიდა (erti bichi movida) a boy arrived (explicitly indefinite)

Using ერთი (erti) emphasizes that the noun is new information and not previously known to the listener.

Articles in Georgian

Adjectives in Georgian

Adjectives in Georgian function similarly to those in many other languages: they describe qualities, characteristics, and states of nouns. However, Georgian adjectives have several unique grammatical features, including their flexibility in sentence structure, their ability to take plural and case suffixes, and the formation of comparative and superlative forms.

Unlike in many Indo-European languages, Georgian adjectives do not change based on gender. There are no separate forms for masculine or feminine nouns, making adjective usage more straightforward in this regard.

Placement of Adjectives

Adjectives in Georgian are typically placed before the noun they modify, but they can also appear after the noun without changing meaning.

Examples:

ლამაზი სახლი (lamazi sakhli) a beautiful house

დიდი ქალაქი (didi kalaki) a big city

ახალი წიგნი (akhali tsigni) a new book

The adjective can also come after the noun, though this is more common in poetic or formal language:

სახლი ლამაზია (sakhli lamazia) the house is beautiful

ქალაქი დიდია (kalaki didia) the city is big

The word order does not significantly change the meaning, but adjectives are more commonly placed before nouns in everyday speech.

Agreement of Adjectives with Nouns

Adjectives in Georgian must agree with the noun in case and number. This means that when a noun changes due to its grammatical role in the sentence, the adjective must also change accordingly.

Singular and Plural Forms

The plural of adjectives is formed by adding -ები (-ebi) or -ნი (-ni), depending on the noun’s plural form.

Examples:

ლამაზი გოგო (lamazi gogo) a beautiful girl → ლამაზი გოგოები (lamazi gogoebi) beautiful girls

დიდი სახლი (didi sakhli) a big house → დიდი სახლები (didi sakhlebi) big houses

სწრაფი მანქანა (sts’rapi mankana) a fast car → სწრაფი მანქანები (sts’rapi mankanebi) fast cars

The adjective remains unchanged in most cases except for pluralization when necessary.

Adjectives and Case Marking

Just like nouns, adjectives in Georgian take case suffixes depending on their function in a sentence. The case endings applied to adjectives generally match those applied to nouns.

Examples of Adjectives in Different Cases

Nominative Case (subject of a sentence):

ლამაზი ბაღი არის დიდი (lamazi baghi aris didi) the beautiful garden is big

Dative Case (indirect object, certain verb constructions):

მიჭირს დიდ ქალაქში ცხოვრება (michirs did kalakshi tskhovreba) it is difficult for me to live in a big city

Genitive Case (possession or relation):

ლამაზი ბაღის ყვავილები (lamazi baghis qvavilebi) the flowers of the beautiful garden

Instrumental Case (used with means or method):

მხიარული ხმით მღეროდა (mkhiaruli khmit mgheroda) he/she was singing with a cheerful voice

Adverbial Case (describing a state or manner):

ბავშვი მხიარულად თამაშობდა (bavshvi mkhiarulad tamashobda) the child was playing happily

Adjective case changes are most noticeable in genitive, dative, and instrumental cases, where adjectives receive case suffixes similar to those of nouns.

Comparative and Superlative Forms

In Georgian, comparatives and superlatives are formed differently than in English. There are no special endings for adjectives to indicate "more" or "most", and instead, additional words are used.

Comparative (More… than …)

Comparisons in Georgian are typically formed using უფრო (upro) meaning more, followed by the adjective.

Examples:

ეს სახლი უფრო დიდია, ვიდრე ის (es sakhli upro didia, vidre is) this house is bigger than that one

მარიამი უფრო სწრაფია, ვიდრე გიორგი (mariami upro sts’rapia, vidre giorgi) Mariam is faster than Giorgi

ეს წიგნი უფრო საინტერესოა (es tsigni upro sainteresoia) this book is more interesting

The word ვიდრე (vidre) or ქონე (kone) is used to mean "than" in comparisons.

Superlative (Most … / The …-est)

To form the superlative, the word ყველაზე (qvelaze) meaning the most is placed before the adjective.

Examples:

ეს არის ყველაზე დიდი ქალაქი (es aris qvelaze didi kalaki) this is the biggest city

ყველაზე ლამაზი ყვავილი (qvelaze lamazi qvavili) the most beautiful flower

ეს ბავშვი ყველაზე მხიარულია (es bavshvi qvelaze mkhiarulia) this child is the happiest

There is no separate adjective form to express comparative or superlative, unlike in English (bigger, biggest). Instead, the words "უფრო" (upro) and "ყველაზე" (qvelaze) are used.

Adjective-Derived Words and Intensification

Many Georgian adjectives have related words that express different degrees of intensity or change their meaning slightly.

Diminutive and Augmentative Forms

Some adjectives can be modified to diminutive (less intense) or augmentative (stronger intensity) forms using suffixes:

მცირედი (mts’iredi) a little bit small (from პატარა (patara) small)

ძალიან დიდი (dzalian didi) very big

Prefixes for Strengthening Meaning

Some adjectives gain prefixes to intensify their meaning:

უძლიერესი (udzlieresi) extremely strong (from ძლიერი (dzlieri) strong)

უსუფთაო (usup’tao) completely clean (from სუფთა (supta) clean)

Pronouns in Georgian

Pronouns are an essential part of Georgian grammar, just as they are in many other languages. They are used to replace nouns and refer to people, objects, or ideas without repeating the same words. Georgian pronouns function similarly to those in English, but they also have unique features, such as case changes, special verb agreement, and the absence of grammatical gender.

Georgian pronouns are divided into several categories, including personal pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, possessive pronouns, interrogative pronouns, indefinite pronouns, and reflexive pronouns.

Personal Pronouns

Personal pronouns in Georgian are used to refer to specific people or things. Unlike in English, where pronouns change based on gender (he/she), Georgian pronouns do not indicate gender. This means that ის (is) can mean both he and she depending on the context.

Singular Personal Pronouns

მე (me) I

შენ (shen) you (singular)

ის (is) he / she / it

Plural Personal Pronouns

ჩვენ (chven) we

თქვენ (tkven) you (plural or formal)

ისინი (isini) they

Georgian does not require the use of personal pronouns in every sentence because verb conjugation already indicates the subject. For example:

მუშაობ (mush'aob) you are working – The "you" is already implied by the verb form.

მივდივარ (mividivar) I am going – The verb already includes the meaning of I.

However, personal pronouns can be used for emphasis:

მე ვმუშაობ (me vmushaob) I am working (emphasizing I rather than someone else).

ის წავიდა (is ts’avida) he/she left (clarifying who left).

Personal Pronouns in Different Cases

Like nouns, personal pronouns change form depending on their grammatical function in a sentence. This happens due to the case system in Georgian.

For example, the pronoun "I" (მე me) changes to "me" (მეს me-s) when used in the dative case.

მე მჭირდება ფული (me mchirdeba puli) I need money

შენ გიყვარს მუსიკა (shen giqvars musika) you love music

Since verbs often incorporate pronoun markers, standalone pronouns are not always necessary.

Possessive Pronouns

Possessive pronouns indicate ownership. In Georgian, they are placed before the noun they modify and agree in number (singular or plural).

Singular Possessive Pronouns

ჩემი (chemi) my

შენი (sheni) your (singular)

მისი (misi) his / her / its

Plural Possessive Pronouns

ჩვენი (chveni) our

თქვენი (tkveni) your (plural/formal)

მათი (mati) their

Examples:

ჩემი მეგობარი (chemi megobari) my friend

შენი სახლი (sheni sakhli) your house

მისი ძაღლი (misi dzaghli) his/her dog

ჩვენი სკოლა (chveni skola) our school

თქვენი მანქანა (tkveni mankana) your car

Possessive pronouns do not change for gender. The same word მისი (misi) is used for his, her, and its.

Possession can also be expressed using genitive constructions:

ბიჭის წიგნი (bichis tsigni) the boy’s book

ქალის ჩანთა (kalis chanta) the woman’s bag

Demonstrative Pronouns

Demonstrative pronouns point to specific things. Georgian has two main demonstrative pronouns:

ეს (es) this

ის (is) that

Examples:

ეს წიგნია (es tsignia) this is a book

ის კაცია (is katsia) that is a man

მიყვარს ეს ფილმი (miqvars es pilmi) I love this movie

ის ქალაქი ძალიან დიდია (is kalaki dzalian didia) that city is very big

Unlike English, Georgian does not have a separate word for "these" or "those". Instead, plurality is indicated by the plural form of the noun:

ეს წიგნები (es tsignebi) these books

ის მანქანები (is mankanebi) those cars

Interrogative Pronouns

Interrogative pronouns are used to ask questions.

ვინ (vin) who

რა (ra) what

რომელი (romeli) which

ვისი (visi) whose

სად (sad) where

როდის (rodis) when

რატომ (ratom) why

როგორ (rogor) how

Examples:

ვინ არის ის? (vin aris is?) Who is he/she?

რა გინდა? (ra ginda?) What do you want?

რომელი მანქანა მოგწონს? (romeli mankana mogts’ons?) Which car do you like?

ვისია ეს ჩანთა? (visia es chanta?) Whose bag is this?

Indefinite Pronouns

Indefinite pronouns refer to non-specific people or things.

ვიღაც (vighats) someone

რამე (rame) something

არავინ (aravin) no one

არაფერი (araferi) nothing

ყველა (qvela) everyone

ყველაფერი (qvelaperi) everything

Examples:

ვიღაც მოგძებნა (vighats mogdzebna) someone was looking for you

რამე გაბედე? (rame gabede?) did you try something?

არავინ მოვიდა (aravin movida) no one came

ყველა აქ არის (qvela ak aris) everyone is here

Reflexive Pronouns

Reflexive pronouns refer back to the subject of the sentence. Georgian uses თავი (tavi) self for this purpose.

მე ვხედავ ჩემს თავს (me vkhedav chems tavs) I see myself

ის გრძნობს თავის თავს უბედურად (is grdznobs tavis tavs ubedurad) he/she feels unhappy

ჩვენ ვამაყობთ ჩვენს თავით (chven vamakobt chvens tavit) we are proud of ourselves

Prepositions in Georgian

In many languages, prepositions (such as in, on, under, behind) are used to indicate the relationship between words. However, Georgian does not use prepositions in the same way as English or other Indo-European languages. Instead, it uses postpositions—grammatical elements that come after the noun rather than before it.

Postpositions in Georgian function similarly to English prepositions but attach to the noun in different grammatical cases, most often the genitive, dative, or instrumental case. Many postpositions are short suffix-like elements, while others are longer separate words.

How Postpositions Work in Georgian

Unlike in English, where we say:

on the table

under the bridge

with a friend

In Georgian, the postposition follows the noun, and the noun changes case accordingly.

For example:

მაგიდაზე (magidaze) on the table

ხიდის ქვეშ (khidis kvesh) under the bridge

მეგობართან ერთად (megobartan ertad) with a friend

Each postposition requires a specific noun case, and these relationships must be learned individually.

Types of Postpositions in Georgian

Georgian postpositions can be grouped based on their function: locational postpositions, directional postpositions, instrumental postpositions, and postpositions expressing relationships.

Locational Postpositions

These postpositions describe the location of something and are usually attached to a noun in the genitive case.

Common Locational Postpositions

ზემოთ (zemot) above

ქვეშ (kvesh) under, beneath

შიგნით (shignit) inside

გარეთ (garet) outside

გარშემო (garshemo) around

შუაში (shuashi) in the middle of

გვერდით (gverdit) next to, beside

Examples

ცაზე ვარსკვლავებია (tsaze varskvlavebia) there are stars in the sky

დივნის ქვეშ კატა ზის (divnis kvesh kata zis) the cat is sitting under the sofa

ქალაქის შუაში არის პარკი (kalakis shuashi aris parki) in the middle of the city, there is a park

ბავშვები მაგიდის გარშემო სხედან (bavshvebi magidis garshemo skhedan) the children are sitting around the table

Directional Postpositions

Directional postpositions indicate movement toward or away from a place. They commonly attach to nouns in the genitive or dative case.

Common Directional Postpositions

მიმართულებით (mimartulebit) toward

მიღმა (mighma) beyond

დაკენ (daken) towards

განმავლობაში (ganmavlobashi) throughout

მდებარეობაში (mdgheorobashi) into (a position)

Examples

ქალაქისკენ წავედით (kalakisk’en ts’avidit) we went toward the city

მდინარის მიღმა ტყეა (mdinaris mighma t’qea) beyond the river, there is a forest

მისი კარიერის განმავლობაში ბევრი იმუშავა (misi karieris ganmavlobashi beuri imusha) throughout his career, he worked a lot

Instrumental and Means Postpositions

These postpositions indicate how something is done or with what instrument. They require the instrumental case (usually marked with -ით (-it)).

Common Instrumental Postpositions

მეშვეობით (meshveobit) by means of

მიერ (mier) by (agent of action)

დახმარებით (dakhmarebit) with the help of

გამოყენებით (gamokenebit) using

Examples

მანქანით ვიმგზავრე (mankanit vimgzavre) I traveled by car

ბიჭის მიერ გაკეთდა (bichis mier gaketda) it was done by the boy

პროექტი დაფინანსდა მთავრობის მეშვეობით (proekti dapinansda mtavrobis meshveobit) the project was funded by the government

Postpositions Expressing Relationships

These postpositions indicate associations, comparisons, and relationships between nouns.

Common Relationship Postpositions

ერთად (ertad) together with

თან (tan) with

დაკავშირებით (dakavshirebit) regarding

შესახებ (shesakheb) about

გამო (gamo) because of

Examples

მეგობრებთან ერთად წავედი (megobrebtan ertad ts’avedi) I went with friends

განსხვავებით მისი ძმისგან (ganskhorvebit misi dzmisan) different from his brother

ამ თემასთან დაკავშირებით ბევრი კითხვა მაქვს (am temas tan dakavshirebit beuri kitkhva makvs) I have many questions regarding this topic

შენზე ვფიქრობ (shenze vphiqrob) I am thinking about you

Postpositions and Verb Agreement

Some postpositions influence the verb structure in a sentence.

For example, when using ერთად (ertad) or თან (tan) (with), the verb often takes a plural or indirect object construction:

ბავშვები დედასთან ერთად წავიდნენ (bavshvebi dedastan ertad ts’avidnen) the children went with their mother

With გამო (gamo) (because of), verbs often imply causation:

წვიმის გამო არ წავედით (ts’vimis gamo ar ts’avidit) because of the rain, we didn’t go

Adverbs are an essential part of the Georgian language, modifying verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs to express manner, time, place, degree, and frequency. Unlike nouns, adjectives, and verbs, adverbs do not decline or change form based on case or agreement. This makes them relatively straightforward compared to other parts of Georgian grammar.

Georgian adverbs often have specific suffixes, but many are formed directly from adjectives or as independent words. Understanding adverbs is crucial for building natural and expressive sentences in Georgian.

Formation of Adverbs in Georgian

There are three main ways to form adverbs in Georgian:

Independent Adverbs – words that exist solely as adverbs.

Adjective-Derived Adverbs – formed by modifying adjectives.

Postpositional Adverbs – formed by adding postpositions to nouns.

1. Independent Adverbs

Some adverbs in Georgian do not derive from adjectives or other parts of speech but exist as standalone words.

Examples of Independent Adverbs

კარგად (k’argad) well

ცუდად (ts’udad) badly

სწრაფად (sts’rapad) quickly

ნელა (nela) slowly

ახლა (akhla) now

მერე (mere) later

აქ (ak) here

იქ (ik) there

ყოველთვის (qoveltvis) always

ხშირად (kshirat) often

These adverbs do not change form regardless of their position in a sentence.

Examples in Sentences

ის ქართულს კარგად ლაპარაკობს (is kartuls k’argad lap’arakobs) he/she speaks Georgian well

გუშინ ძალიან ცივიდა (gushin dzalian tsivida) yesterday it was very cold

შენ აქ იყავი? (shen ak iqavi?) were you here?

2. Adjective-Derived Adverbs

Many adverbs in Georgian are formed from adjectives by adding specific suffixes, most commonly -ად (-ad) or -ულად (-ulad).

Formation from Adjectives

ლამაზი (lamazi) beautiful → ლამაზად (lamazad) beautifully

სწორი (sts’ori) correct → სწორად (sts’orad) correctly

მხიარული (mkhiaruli) cheerful → მხიარულად (mkhiarulad) cheerfully

ენერგიული (energuli) energetic → ენერგიულად (energulad) energetically

Examples in Sentences

ის მხიარულად მღერის (is mkhiarulad mgherisi) he/she sings cheerfully

დედამ საჭმელი გემრიელად მოამზადა (dedam sach’meli gemrielad moamzada) mother prepared the food deliciously

ლექტორმა სწრაფად უპასუხა კითხვას (lekt’orma sts’rapad up’asukha kit’kvas) the lecturer answered the question quickly

This pattern is very productive, and many adjectives in Georgian can form adverbs in this way.

3. Postpositional Adverbs

Some adverbs are created using postpositions attached to nouns. These function like prepositional phrases in English, giving information about location, direction, or manner.

Examples of Postpositional Adverbs

თვალდახუჭულად (tvaldakhuchelad) blindly (lit. "with closed eyes")

ხელით (khelit) by hand

ფეხით (pekhit) on foot

თავდაყირა (tavdaq’ira) upside-down

ცივად (ts’ivad) coldly

Examples in Sentences

ის ფეხით წამოვიდა (is pekhit tsamovida) he/she came on foot

შენ თვალდახუჭულად ენდობი? (shen tvaldakhuchelad endobi?) do you trust blindly?

ცივად მომექცა (ts’ivad momeq’tsa) he/she treated me coldly

Postpositional adverbs can sometimes be idiomatic and are often used in informal or figurative speech.

Types of Adverbs in Georgian

Georgian adverbs can be categorized based on their function: manner, place, time, degree, and frequency.

1. Adverbs of Manner (How?)

These adverbs describe how something happens.

Common Examples

სწორად (sts’orad) correctly

მშვიდად (mshvidad) calmly

დახვეწილად (dakhvets’ilad) elegantly

უხეშად (ukheshad) rudely

ემოციურად (emotsiurad) emotionally

Examples in Sentences

ის მშვიდად ლაპარაკობს (is mshvidad lap’arakobs) he/she speaks calmly

ბავშვმა უხეშად მიპასუხა (bavshvma ukheshad mipasukha) the child answered me rudely

2. Adverbs of Place (Where?)

These adverbs indicate location.

Common Examples

აქ (ak) here

იქ (ik) there

სადღაც (sadghats) somewhere

ყველგან (qvelgan) everywhere

ახლოს (akhlos) near

Examples in Sentences

მანქანა აქ დგას (mankana ak dgas) the car is standing here

ის სადღაც წავიდა (is sadghats ts’avida) he/she went somewhere

3. Adverbs of Time (When?)

These adverbs describe when something happens.

Common Examples

ახლა (akhla) now

გუშინ (gushin) yesterday

ხვალ (khval) tomorrow

მალე (male) soon

ყოველდღე (qoveldghe) every day

Examples in Sentences

გუშინ თოვდა (gushin tovda) yesterday it snowed

ხვალ გამოცდა მაქვს (khval gamotsda makvs) tomorrow I have an exam

4. Adverbs of Degree (How much?)

These adverbs intensify or limit the action.

Common Examples

ძალიან (dzalian) very

თითქმის (titkmis) almost

სრულიად (sruliad) completely

ნაწილობრივ (nats’ilobriv) partially

Examples in Sentences

ეს ძალიან საინტერესოა (es dzalian sainteresoia) this is very interesting

ნაწილობრივ გეთანხმები (nats’ilobriv get’ankhmebi) I partially agree with you

5. Adverbs of Frequency (How often?)

These adverbs indicate how often something happens.

Common Examples

ყოველთვის (qoveltvis) always

ხშირად (kshirat) often

იშვიათად (ishviatad) rarely

ზოგჯერ (zogjer) sometimes

Examples in Sentences

ის ყოველთვის ადრე იღვიძებს (is qoveltvis adre igvidzebs) he/she always wakes up early

ზოგჯერ წიგნს ვკითხულობ (zogjer ts’igns vkitkhulob) sometimes I read books

Adverbs in Georgian

Present Tense in Georgian

The present tense in Georgian is one of the most essential verb forms, used to describe current actions, general truths, and habitual activities. Unlike English, where the present tense can include multiple forms (I eat, I am eating), Georgian has one main present tense form.

Verbs in the present tense change based on subject pronouns and follow specific conjugation rules. Georgian verbs belong to three conjugation groups, with most verbs in the first conjugation group being transitive (taking a direct object) and intransitive (not requiring a direct object).

Each verb consists of:

A root

A present tense prefix (sometimes omitted)

A subject agreement marker

A verb ending

Conjugating a Regular Verb in the Present Tense

Let’s take the verb წერა (ts’era) to write as an example and conjugate it for all personal pronouns.

Present Tense of "წერა" (to write)

მე ვწერ (me vts’er) I write

შენ წერ (shen ts’er) you write

ის წერს (is ts’ers) he/she/it writes

ჩვენ ვწერთ (chven vts’ert) we write

თქვენ წერთ (tkven ts’ert) you (plural/formal) write

ისინი წერენ (isini ts’eren) they write

Observations:

The prefix "ვ-" (v-) appears in first-person singular (მე vts’er) and first-person plural (ჩვენ vts’ert).

The third-person singular (ის ts’ers) adds -ს (-s) at the end.

The third-person plural (ისინი ts’eren) changes the ending to -ენ (-en).

Conjugation of Different Types of Verbs in the Present Tense

Now, let's examine verbs from different verb categories.

Action Verbs (First Conjugation Group)

These are verbs that describe an active process or physical action.

Present Tense of "გაკეთება" (gaketeba) to do / to make

მე ვაკეთებ (me vaketeb) I do / I make

შენ აკეთებ (shen aketeb) you do / you make

ის აკეთებს (is aketebs) he/she does / makes

ჩვენ ვაკეთებთ (chven vaketebt) we do / we make

თქვენ აკეთებთ (tkven aketebt) you (plural/formal) do / make

ისინი აკეთებენ (isini aketeben) they do / make

Present Tense of "სწავლა" (sts’avla) to study / to learn

მე ვსწავლობ (me vsts’avlob) I study

შენ სწავლობ (shen sts’avlob) you study

ის სწავლობს (is sts’avlobs) he/she studies

ჩვენ ვსწავლობთ (chven vsts’avlobt) we study

თქვენ სწავლობთ (tkven sts’avlobt) you (plural/formal) study

ისინი სწავლობენ (isini sts’avloben) they study

Stative Verbs (Second Conjugation Group)

These verbs describe states, conditions, or emotions rather than actions.

Present Tense of "უყვარს" (uqvars) to love / to like

მე მიყვარს (me miqvars) I love / I like

შენ გიყვარს (shen giqvars) you love / you like

მას უყვარს (mas uqvars) he/she loves / likes

ჩვენ გვიყვარს (chven gviqvars) we love / we like

თქვენ გიყვართ (tkven giqvart) you (plural/formal) love / like

მათ უყვართ (mat uqvart) they love / like

Unlike action verbs, stative verbs often do not use prefixes like "ვ-" or "გ-". Instead, they use special subject markers such as "მ-" (m-), "გ-" (g-), "უ-" (u-), etc.

Present Tense of "შეძლება" (shezleba) to be able to / can

მე შემიძლია (me shemidzia) I can

შენ შეგიძლია (shen shegidzlia) you can

მას შეუძლია (mas sheudzlia) he/she can

ჩვენ შეგვიძლია (chven shegvdzlia) we can

თქვენ შეგიძლიათ (tkven shegidzliat) you (plural/formal) can

მათ შეუძლიათ (mat sheudzliat) they can

Verbs Expressing Motion (Third Conjugation Group)

These verbs indicate movement and often have unique conjugation patterns.

Present Tense of "წასვლა" (ts’asvla) to go

მე მივდივარ (me mividivar) I am going

შენ მიდიხარ (shen midikhar) you are going

ის მიდის (is midis) he/she is going

ჩვენ მივდივართ (chven mividivart) we are going

თქვენ მიდიხართ (tkven midikhart) you (plural/formal) are going

ისინი მიდიან (isini midian) they are going

Present Tense of "მოსვლა" (mosvla) to come

მე მოვდივარ (me movidivar) I am coming

შენ მოდიხარ (shen modikhar) you are coming

ის მოდის (is modis) he/she is coming

ჩვენ მოვდივართ (chven movidivart) we are coming

თქვენ მოდიხართ (tkven modikhart) you (plural/formal) are coming

ისინი მოდიან (isini modian) they are coming

Present Tense in Questions and Negative Sentences

Questions

In Georgian, questions do not require auxiliary verbs like English ("Do you write?"). Instead, intonation and word order indicate that a sentence is a question.

წერ? (ts’er?) Do you write?

მიდიხარ სკოლაში? (midikhar skolashi?) Are you going to school?

Negation

To make a verb negative, Georgian adds "არ" (ar) before the verb.

მე არ ვწერ (me ar vts’er) I do not write

შენ არ სწავლობ (shen ar sts’avlob) You do not study

ის არ მოდის (is ar modis) He/she is not coming

The past tense in Georgian is more complex than the present tense because it follows different conjugation patterns depending on verb type and whether the verb is transitive or intransitive. Unlike English, where past tense verbs often take -ed (walked, talked) or have irregular forms (went, ate), Georgian past tense verbs follow a specific structure with unique subject markers.

One important feature of the past tense in Georgian is the use of the ergative case for the subject when dealing with transitive verbs (verbs that take a direct object). In these cases, the subject of the verb appears in the ergative case, while the object is in the nominative case.

Formation of the Past Tense in Georgian

In Georgian, the past tense is formed differently for:

Transitive verbs (verbs that require an object, like to write, to read, to see).

Intransitive verbs (verbs that do not require an object, like to run, to sleep, to arrive).

Stative verbs (verbs expressing emotions or conditions, like to love, to know).

Motion verbs (verbs related to movement, like to go, to come).

Each of these categories has a different way of conjugation in the past tense.

Past Tense of Transitive Verbs

In transitive verbs, the subject takes the ergative case (instead of the nominative), and the verb conjugation is different from the present tense.

Let’s take the verb წერა (ts’era) to write.

Conjugation of "წერა" (to write) in the past tense

მე დავწერე (me davts’ere) I wrote

შენ დაწერე (shen dats’ere) you wrote

მან დაწერა (man dats’era) he/she wrote

ჩვენ დავწერეთ (chven davts’eret) we wrote

თქვენ დაწერეთ (tkven dats’eret) you (plural/formal) wrote

მათ დაწერეს (mat dats’eres) they wrote

Observations:

The subject is in the ergative case (instead of the nominative).

The prefix "და-" (da-) is used.

The third-person singular form ends in -ა (-a) instead of -ს (-s) like in the present tense.

The third-person plural form ends in -ეს (-es).

Other transitive verbs follow this pattern.

Past Tense of "ნახვა" (nakhva) to see

მე დავინახე (me davinakh) I saw

შენ დაინახე (shen dainakh) you saw

მან დაინახა (man dainakha) he/she saw

ჩვენ დავინახეთ (chven davinakhet) we saw

თქვენ დაინახეთ (tkven dainakhet) you (plural/formal) saw

მათ დაინახეს (mat dainakhes) they saw

Past Tense of Intransitive Verbs

For intransitive verbs (verbs that do not require a direct object), the subject remains in the nominative case.

Conjugation of "ცხოვრება" (tskhovreba) to live

მე ვცხოვრობდი (me vtskhovrobdi) I lived

შენ ცხოვრობდი (shen tskhovrobdi) you lived

ის ცხოვრობდა (is tskhovroba) he/she lived

ჩვენ ვცხოვრობდით (chven vtskhovrobdit) we lived

თქვენ ცხოვრობდით (tkven tskhovrobdid) you (plural/formal) lived

ისინი ცხოვრობდნენ (isini tskhovrobdnen) they lived

Unlike transitive verbs, intransitive verbs do not use the "და-" (da-) prefix.

Another common intransitive verb follows the same pattern:

Past Tense of "ძილი" (dzili) to sleep

მე მეძინა (me medzina) I slept

შენ გეძინა (shen gedzina) you slept

მას ეძინა (mas edzina) he/she slept

ჩვენ გვეძინა (chven gvedzina) we slept

თქვენ გეძინათ (tkven gedzinat) you (plural/formal) slept

მათ ეძინათ (mat edzinat) they slept

Past Tense of Stative Verbs

Stative verbs describe states of being, emotions, and conditions. They follow a unique pattern, using personal markers instead of typical verb endings.

Conjugation of "უყვარს" (uqvars) to love / to like

მე მიყვარდა (me miqvarda) I loved

შენ გიყვარდა (shen giqvarda) you loved

მას უყვარდა (mas uqvarda) he/she loved

ჩვენ გვიყვარდა (chven gviqvarda) we loved

თქვენ გიყვარდათ (tkven giqvardat) you (plural/formal) loved

მათ უყვარდათ (mat uqvardat) they loved

Another example:

Past Tense of "შეძლება" (shezleba) to be able to / can

მე შემეძლო (me shemedzlo) I was able to

შენ შეგეძლო (shen shegedzlo) you were able to

მას შეეძლო (mas sheudzlo) he/she was able to

ჩვენ შეგვეძლო (chven shegvedzlo) we were able to

თქვენ შეგეძლოთ (tkven shegedzlot) you (plural/formal) were able to

მათ შეეძლოთ (mat sheudzlot) they were able to

Past Tense of Motion Verbs

Motion verbs have irregular past tense forms.

Conjugation of "წასვლა" (ts’asvla) to go

მე წავედი (me ts’avedi) I went

შენ წახვედი (shen ts’akhvedi) you went

ის წავიდა (is ts’avida) he/she went

ჩვენ წავედით (chven ts’avidit) we went

თქვენ წახვედით (tkven ts’akhvedit) you (plural/formal) went

ისინი წავიდნენ (isini ts’avidnen) they went

Another example:

Past Tense of "მოსვლა" (mosvla) to come

მე მოვედი (me movedi) I came

შენ მოხვედი (shen mokhvedi) you came

ის მოვიდა (is movida) he/she came

ჩვენ მოვედით (chven movedit) we came

თქვენ მოხვედით (tkven mokhvedit) you (plural/formal) came

ისინი მოვიდნენ (isini movidnen) they came

Past Tense in Georgian

Future Tense in Georgian

The future tense in Georgian is used to describe actions that will happen in the future. Unlike English, where the auxiliary verbs will or shall are used to indicate the future, Georgian changes the verb structure itself to mark the future tense.

The future tense is formed by modifying the verb root with a specific future prefix and verb endings that agree with the subject. The structure depends on whether the verb is transitive or intransitive. Additionally, irregular verbs and motion verbs have their own unique future tense patterns.

Formation of the Future Tense in Georgian

To form the future tense, the verb root is modified by:

A future prefix (გა- (ga-), შე- (she-), დაი- (dai-), etc.)

A present-tense verb ending

The most common future prefix is გა- (ga-), though different verbs may use other prefixes.

Future Tense of Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs (verbs that take a direct object) form the future tense by adding a future prefix and conjugating as in the present tense.

Conjugation of "წერა" (ts’era) to write

მე დავწერ (me davts’er) I will write

შენ დაწერ (shen dats’er) you will write

ის დაწერს (is dats’ers) he/she will write

ჩვენ დავწერთ (chven davts’ert) we will write

თქვენ დაწერთ (tkven dats’ert) you (plural/formal) will write

ისინი დაწერენ (isini dats’eren) they will write

Observations:

The prefix "და-" (da-) is used in the future tense.

The first-person singular and plural forms take the "ვ-" (v-) prefix, like in the present tense.

The third-person singular ends in "-ს" (-s), and the third-person plural ends in "-ენ" (-en).

Another Example: Future Tense of "კეთება" (keteba) to do / to make

მე გავაკეთებ (me gavaketeb) I will do / I will make

შენ გააკეთებ (shen gaaketeb) you will do / you will make

ის გააკეთებს (is gaaketebs) he/she will do / will make

ჩვენ გავაკეთებთ (chven gavaketebt) we will do / we will make

თქვენ გააკეთებთ (tkven gaaketebt) you (plural/formal) will do / will make

ისინი გააკეთებენ (isini gaaketeben) they will do / will make

Future Tense of Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive verbs (verbs that do not require an object) also take a future prefix, but they retain their regular present-tense endings.

Conjugation of "ცხოვრება" (tskhovreba) to live

მე ვიცხოვრებ (me vits’khovreb) I will live

შენ იცხოვრებ (shen its’khovreb) you will live

ის იცხოვრებს (is its’khovrebs) he/she will live

ჩვენ ვიცხოვრებთ (chven vits’khovrebt) we will live

თქვენ იცხოვრებთ (tkven its’khovrebt) you (plural/formal) will live

ისინი იცხოვრებენ (isini its’khovreben) they will live

Unlike transitive verbs, intransitive verbs do not take the "და-" (da-) prefix but instead change the root vowel or take a new prefix.

Another Example: Future Tense of "დახმარება" (dakhmareba) to help

მე დავეხმარები (me davekhmarebi) I will help

შენ დაეხმარები (shen daekhmarrebi) you will help

ის დაეხმარება (is daekhmarreba) he/she will help

ჩვენ დავეხმარებით (chven davekhmarebit) we will help

თქვენ დაეხმარებით (tkven daekhmarrebit) you (plural/formal) will help

ისინი დაეხმარებიან (isini daekhmarreben) they will help

Future Tense of Stative Verbs

Stative verbs express feelings, states, or abilities. They follow a unique conjugation pattern in the future tense.

Conjugation of "უყვარს" (uqvars) to love / to like

მე მეყვარება (me meqvareba) I will love

შენ გეყვარება (shen geqvareba) you will love

მას ეყვარება (mas eqvareba) he/she will love

ჩვენ გვეყვარება (chven gveqvareba) we will love

თქვენ გეყვარებათ (tkven geqvarebat) you (plural/formal) will love

მათ ეყვარებათ (mat eqvarebat) they will love

Since stative verbs use dative personal markers, their future tense does not use "გა-" (ga-) or "და-" (da-).

Another Example: Future Tense of "შეძლება" (shezleba) to be able to / can

მე შემეძლება (me shemedzleba) I will be able to

შენ შეგეძლება (shen shegedzleba) you will be able to

მას შეეძლება (mas sheudzleba) he/she will be able to

ჩვენ შეგვეძლება (chven shegvedzleba) we will be able to

თქვენ შეგეძლებათ (tkven shegedzlebat) you (plural/formal) will be able to

მათ შეეძლებათ (mat sheudzlebat) they will be able to

Future Tense of Motion Verbs

Motion verbs (verbs that indicate movement) have irregular future tense forms.

Conjugation of "წასვლა" (ts’asvla) to go

მე წავალ (me ts’aval) I will go

შენ წახვალ (shen ts’akhval) you will go

ის წავა (is ts’ava) he/she will go

ჩვენ წავალთ (chven ts’avalt) we will go

თქვენ წახვალთ (tkven ts’akhvalt) you (plural/formal) will go

ისინი წავლენ (isini ts’avlen) they will go

Another Example: Future Tense of "მოსვლა" (mosvla) to come

მე მოვალ (me moval) I will come

შენ მოხვალ (shen mokhval) you will come

ის მოვა (is mova) he/she will come

ჩვენ მოვალთ (chven movalt) we will come

თქვენ მოხვალთ (tkven mokhvalt) you (plural/formal) will come

ისინი მოვლენ (isini movlen) they will come

The imperative mood in Georgian is used to give commands, make requests, offer suggestions, or encourage actions. Just like in English, the imperative can be used in both positive (telling someone to do something) and negative (telling someone not to do something) forms.

The Georgian imperative is particularly important because it changes depending on who is being addressed (singular or plural) and how formal or informal the situation is. Additionally, it can also be used in a polite or indirect way to soften commands.

Formation of the Imperative in Georgian

The imperative is formed by modifying the verb stem and adding appropriate endings. The key features of the imperative in Georgian include:

The basic imperative form is usually derived from the verb root.

Singular commands have a distinct form from plural or polite commands.

Some verbs use prefixes or changes in the verb stem to form the imperative.

The negative imperative is formed by adding "არ" (ar) before the verb.

Imperative for Singular "You"

When giving a command to one person, the verb typically appears in its simplest root form, sometimes with a vowel change.

Examples:

წაიკითხე წიგნი (ts’aikitkhe ts’igni) read the book!

დაჯექი სკამზე (dajek’i skamze) sit on the chair!

მომეცი ფული (mometsi puli) give me the money!

მიდი სახლში (midi sakhlshi) go home!

არ ილაპარაკო (ar ilaparako) don’t talk!

The negative imperative (telling someone not to do something) is formed by adding "არ" (ar) before the verb.

არ გაიქცე (ar gaik’tse) don’t run!

არ დამავიწყო (ar damavits’qo) don’t forget me!

Imperative for Plural or Formal "You"

When addressing more than one person or using a polite form for one person, the verb takes a different ending. The -თ (-t) suffix is added to indicate plurality or formality.

Examples:

წაიკითხეთ წიგნი (ts’aikitkhet ts’igni) read the book!

დაჯექით სკამზე (dajek’it skamze) sit on the chair!

მომეცით ფული (mometit puli) give me the money!

წადით სახლში (ts’adit sakhlshi) go home!

არ ილაპარაკოთ (ar ilaparakot) don’t talk!

This form is commonly used when speaking politely or addressing a group of people.

Imperative for "Let’s"

When suggesting an action for "us" (we), the imperative takes a different form, usually adding the -თ (-t) suffix or using a special verb formation.

Examples:

წავიდეთ კინოში (ts’avidet kinoshi) let’s go to the cinema!

დავჯდეთ აქ (davjdet ak) let’s sit here!

ვიმღეროთ ერთად (vimgherot ertad) let’s sing together!

ვიმუშაოთ ხვალ (vimuashot khval) let’s work tomorrow!

არ დავიწყოთ ახლა (ar davits’qot akhla) let’s not start now!

This form is often used for suggestions or group actions.

Imperative for "Let Them"

To give a command to a third person (e.g., "let him/her/them do something"), a different form is used. The verb is usually formed using a "ჰ-" (h-) prefix for third-person commands.

Examples:

წავიდეს სახლში (ts’avides sakhlshi) let him/her go home!

დაჯდეს სკამზე (dajdes skamze) let him/her sit on the chair!

იმღერონ ერთად (imgheron ertad) let them sing together!

გათავისუფლდეს სამუშაოდან (gatavisup’ldes samushiodan) let him/her be freed from work!

The negative form is created with "არ" (ar) before the verb:

არ წავიდეს (ar ts’avides) let him/her not go!

არ გაიქცნენ (ar gaik’tsnen) let them not run!

Softening the Imperative (Polite Requests)

In formal situations, commands can sound too direct. To soften the imperative, Georgian often uses:

გთხოვ (gt’khov) – please (informal)

გთხოვთ (gt’khovt) – please (formal/plural)

თუ შეიძლება (tu sheidzleba) – if possible / may I

Examples:

გთხოვ, გააკეთე ეს (gt’khov, gaak’ete es) please do this!

გთხოვთ, დამელოდეთ (gt’khovt, damelodet) please wait for me!

თუ შეიძლება, მომეცით წიგნი (tu sheidzleba, mometit ts’igni) if possible, please give me the book

Using these words makes the command polite and respectful.

Common Imperative Verbs in Georgian

Here are some of the most common verbs used in the imperative form:

Basic Commands

მოდი! (modi) come!

წადი! (ts’adi) go!

დაჯექი! (dajek’i) sit down!

ადექი! (adek’i) stand up!

დაამთავრე! (daamtavre) finish it!

Requests and Suggestions

დამეხმარე! (damekhmare) help me!

გამომიგზავნე! (gamomigzavne) send me (something)!

დავიწყოთ! (davits’qot) let’s start!

არ დაგვიანო! (ar dagviano) don’t be late!

Prohibitions (Negative Commands)

არ ეჩხუბო! (ar ech’khubo) don’t argue!

არ ისაუბრო! (ar isaubro) don’t speak!

არ შეეხო! (ar sheekho) don’t touch!

Imperative in Georgian

Passive in Georgian

The passive voice in Georgian is an essential grammatical structure used to indicate that the subject of the sentence is not the doer of the action but instead receives the action. This contrasts with the active voice, where the subject performs the action.

The passive voice is widely used in formal writing, storytelling, and descriptions, and it often allows for more emphasis on the action itself rather than on who is performing it.

Formation of the Passive Voice in Georgian

The passive voice is usually formed by:

Adding specific passive markers to the verb, most commonly -დ (-d), -ილ (-il), or -ულ (-ul).

Using the third conjugation group, which focuses on the subject being affected rather than the agent.

Changing verb agreement so that the subject is in the nominative case instead of the ergative.

Passive constructions in Georgian can be formed in different tenses:

Present Passive

Past Passive

Future Passive

Each tense follows its own rules but maintains the general structure of shifting focus from the agent to the receiver of the action.

The Present Passive

In the present passive, the verb takes a passive suffix, and the subject (the thing being affected) stays in the nominative case.

Conjugation of "დაწერა" (dats’era) to be written

მე ვწერები (me vts’eri) I am being written

შენ წერები (shen ts’eri) you are being written

ის იწერება (is its’ereba) he/she/it is being written

ჩვენ ვწერებით (chven vts’erit) we are being written

თქვენ წერებით (tkven ts’erit) you (plural/formal) are being written

ისინი იწერებიან (isini its’erebian) they are being written

Observations:

The verb root წერ (ts’er) remains, but passive markers are added.

The third-person singular and plural forms use "ი-" (i-) as a passive prefix.

The verb conjugates like an intransitive verb, meaning the subject is in the nominative case rather than the ergative case (used for transitive verbs in the active voice).

Examples in Sentences:

წიგნი იწერება (tsigni its’ereba) the book is being written.

გაკვეთილი ტარდება სკოლაში (gakvetili tardeba skolashi) the lesson is being conducted at school.

ქალაქი შენდება (kalaki shendeba) the city is being built.

The Past Passive

The past passive voice is used when something has already been completed and was not performed by the subject itself.

Conjugation of "დაწერა" (dats’era) to have been written

მე დავწერე (me davts’ere) I was written

შენ დაწერე (shen dats’ere) you were written

ის დაიწერა (is daits’era) he/she/it was written

ჩვენ დავწერეთ (chven davts’eret) we were written

თქვენ დაწერეთ (tkven dats’eret) you (plural/formal) were written

ისინი დაიწერეს (isini daits’eres) they were written

Examples in Sentences:

წერილი დაიწერა გუშინ (tserili daits’era gushin) the letter was written yesterday.

გადაწყვეტილება მიღებულ იქნა (gadats’qvetileba mighebul ikna) the decision was made.

სახლი აშენდა შარშან (sakhli ashenda sharsan) the house was built last year.

The Future Passive

The future passive voice is used to describe something that will happen in the future without specifying who will perform the action.

Conjugation of "დაწერა" (dats’era) to be written in the future

მე დავიწერები (me davits’erebi) I will be written

შენ დაიწერები (shen daits’erebi) you will be written

ის დაიწერება (is daits’ereba) he/she/it will be written

ჩვენ დავიწერებით (chven davits’erebit) we will be written

თქვენ დაიწერებით (tkven daits’erebit) you (plural/formal) will be written

ისინი დაიწერებიან (isini daits’erebian) they will be written

Examples in Sentences:

გეგმა დაიწერება ხვალ (gegma daits’ereba khval) the plan will be written tomorrow.

შეკითხვა გაიცემა მოგვიანებით (shekitkhva gaitsema mogvianebit) the question will be answered later.

ბინა აშენდება მომავალი წლის ბოლოს (bina ashendeba momavali tslis bolos) the apartment will be built by the end of next year.

Using Passive Verbs in Context

Passive constructions are often used in official or formal speech, in news reports, and when the agent (doer) is unknown or unimportant.

Active vs. Passive Voice Comparison

Active:

მასწავლებელი ხსნის გაკვეთილს (masts’avlebeli khsnis gakvetils) The teacher explains the lesson.

Passive:

გაკვეთილი აიხსნება მასწავლებლის მიერ (gakvetili aikhseneba masts’avleblis mier) The lesson is explained by the teacher.

When to Use the Passive Voice in Georgian

When the doer of the action is unknown or unimportant:

წიგნი დაიწერა (tsigni daits’era) the book was written.

გზა დაიგება მომავალი კვირიდან (gza daigeba momavali kviridan) the road will be paved starting next week.

When the focus is on the action or the result rather than the agent:

ბინა გაყიდულია (bina gayidulia) the apartment is sold.

კარი დახურულია (kari dakhurulia) the door is closed.

In formal or legal language:

გადაწყვეტილება მიღებულ იქნა მთავრობის მიერ (gadats’qvetileba mighebul ikna mtavrobis mier) the decision was made by the government.

კანონი დამტკიცდა პარლამენტის მიერ (kanoni damtkits’da parlamentis mier) the law was approved by the parliament.

Negation in Georgian is an essential aspect of sentence formation and follows specific grammatical rules depending on the verb tense, sentence type, and structure. Unlike in English, where negation is typically formed with the auxiliary verb not (e.g., I do not know), Georgian uses negative prefixes and sometimes special negation verbs to form negative statements.

Negation in Georgian can be used in different contexts, including:

Negating verbs (I do not go, He is not working)

Negating nouns and adjectives (This is not a book, He is not happy)

Negating existence (There is no time)

Double negation (Nobody does anything)

Basic Negation with Verbs

Negating Present and Future Tenses

In the present and future tenses, negation is formed by placing the prefix "არ" (ar-) before the verb.

Examples with Present Tense

მე არ ვწერ (me ar vts’er) I do not write

შენ არ კითხულობ (shen ar kitkhulob) You do not read

ის არ თამაშობს (is ar tamashobs) He/she does not play

ჩვენ არ ვმუშაობთ (chven ar vmushaobt) We do not work

თქვენ არ ლაპარაკობთ (tkven ar laparakobt) You (plural/formal) do not speak

ისინი არ სწავლობენ (isini ar sts’avloben) They do not study

The prefix "არ-" (ar-) remains unchanged, regardless of the subject or the verb.

Examples with Future Tense

მე არ დავწერ (me ar davts’er) I will not write

შენ არ წაიკითხავ (shen ar ts’aikitkhav) You will not read

ის არ ითამაშებს (is ar itamashebs) He/she will not play

ჩვენ არ ვიმუშავებთ (chven ar vimushavebt) We will not work

თქვენ არ ისაუბრებთ (tkven ar isaubrebt) You (plural/formal) will not speak

ისინი არ ისწავლიან (isini ar ist’vlian) They will not learn

Negating Past Tense Verbs

Unlike the present and future tenses, past tense negation is often formed with the prefix "არ" (ar-) for intransitive verbs and "არ" (ar-) or "ვერ" (ver-) for transitive verbs.

Examples with Past Tense (Regular Negation with "არ-")

მე არ ვწერდი (me ar vts’erdi) I was not writing

შენ არ კითხულობდი (shen ar kitkhulobdi) You were not reading

ის არ თამაშობდა (is ar tamashobda) He/she was not playing

ჩვენ არ ვმუშაობდით (chven ar vmushaobdit) We were not working

თქვენ არ ლაპარაკობდით (tkven ar laparakobdit) You (plural/formal) were not speaking

ისინი არ სწავლობდნენ (isini ar sts’avlobdnen) They were not studying

Examples with "ვერ" (ver-) for Inability in the Past

The prefix "ვერ-" (ver-) is used when referring to an inability to perform an action, rather than a simple negation.

მე ვერ დავწერე (me ver davts’ere) I could not write

შენ ვერ წაიკითხე (shen ver ts’aikitkhe) You could not read

ის ვერ ითამაშა (is ver itamasha) He/she could not play

ჩვენ ვერ ვიმუშავეთ (chven ver vimushavet) We could not work

თქვენ ვერ ისაუბრეთ (tkven ver isaubret) You (plural/formal) could not speak

ისინი ვერ ისწავლეს (isini ver ist’vles) They could not learn

The main difference between "არ-" (ar-) and "ვერ-" (ver-) is that "არ-" simply negates the verb, whereas "ვერ-" implies an inability to do something.

2. Negation with Nouns and Adjectives

When negating nouns or adjectives, the prefix "არ-" (ar-) or "უ-" (u-) is added.

Examples with Nouns

ეს არ არის წიგნი (es ar aris ts’igni) This is not a book

ის არ არის ექიმი (is ar aris ek’imi) He/she is not a doctor

ეს არ არის პრობლემა (es ar aris problema) This is not a problem

Examples with Adjectives

ის არ არის ლამაზი (is ar aris lamazi) He/she is not beautiful

ეს სახლი არ არის დიდი (es sakhli ar aris didi) This house is not big

მე არ ვარ ბედნიერი (me ar var bednieri) I am not happy

For permanent qualities, the prefix "უ-" (u-) is sometimes added to form a negative adjective.

უნიჭო ადამიანი (unicho adamiani) a talentless person

უდიდესი შეცდომა (udidesi shetsdoma) a very big mistake

უღიმღამო დღე (ughimghamo dghe) a dull day

Negation of Existence ("There is no…")

To express non-existence, Georgian uses the word "არ არის" (ar aris) or "არ არის" (aris ar)".

აქ წყალი არ არის (ak ts’qali ar aris) There is no water here

ფული არ არის (puli ar aris) There is no money

აქ არავინაა (ak aravinaa) There is no one here

A shortened, more colloquial form of "არ არის" (ar aris) is "არაა" (araa).

Double Negation in Georgian

In Georgian, double negation is common and is required for negative pronouns like nobody, nothing, never.

არავინ არ მოვიდა (aravin ar movida) Nobody came

არაფერი არ მინახავს (araferi ar minakhavs) I have seen nothing

არასდროს არ მელაპარაკა (arasdros ar melap’arak’a) He/she never talked to me

The negative pronouns require "არ-" (ar-) to complete the meaning.

Negation in Commands and Imperatives

To form negative commands in Georgian, the prefix "არ" (ar-) is used before the verb.

Examples

არ თქვა (ar t’qva) Do not say!

არ მიბაძო (ar mibadzo) Do not imitate me!

არ გააკეთო ეს! (ar gaak’eto es!) Do not do this!

For stronger prohibitions, "ნუ" (nu) is used instead of "არ".

ნუ ყვირი! (nu qviri!) Do not shout!

ნუ ინერვიულებ! (nu inerviuleb!) Do not worry!

ნუ შეწუხდები! (nu shets’uk’debi!) Do not bother!

Negation in Georgian

Word Order Alphabet

Word order in Georgian is significantly more flexible than in English and many other languages. This is because Georgian is an inflected language, meaning that the role of each word in a sentence is determined by case markers rather than strict word positioning.

While the default word order in Georgian is Subject-Object-Verb (SOV), it can change depending on emphasis, focus, and stylistic choices. The verb almost always comes at the end of the sentence, but word order before the verb is quite flexible.

Default Word Order: Subject-Object-Verb

In neutral sentences (without special emphasis), Georgian follows the SOV structure, where the subject comes first, the object follows, and the verb is placed at the end.

Examples

ბიჭი წიგნს კითხულობს (bichi ts’igns kitkhulobs) The boy is reading a book.

ბიჭი (bichi) boy (subject)

წიგნს (ts’igns) book (object)

კითხულობს (kitkhulobs) is reading (verb)

მასწავლებელი ბავშვებს ასწავლის (masts’avlebeli bavshvebs asts’avlis) The teacher teaches the children.

მასწავლებელი (masts’avlebeli) teacher (subject)

ბავშვებს (bavshvebs) children (object)

ასწავლის (asts’avlis) teaches (verb)

Since the case endings clarify the grammatical roles of each noun, the order of words can often be changed without affecting the meaning.

Alternative Word Orders for Emphasis

In spoken and literary Georgian, word order can be changed to emphasize different parts of the sentence.

Object-Subject-Verb (OSV) – Emphasizing the Object

წიგნს ბიჭი კითხულობს (ts’igns bichi kitkhulobs) It is the book that the boy is reading.

The object (წიგნს ts’igns – "book") is placed before the subject to emphasize what is being read.

Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) – More Natural in Speech

ბიჭი კითხულობს წიგნს (bichi kitkhulobs ts’igns) The boy is reading a book.

This order is more common in spoken Georgian, even though SOV is the neutral order.

Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) – Used in Questions or Exclamations

კითხულობს ბიჭი წიგნს? (kitkhulobs bichi ts’igns?) Is the boy reading a book?

In questions, the verb often moves to the front.

Object-Verb-Subject (OVS) – Strong Emphasis on the Object

წიგნს კითხულობს ბიჭი (ts’igns kitkhulobs bichi) The book is what the boy is reading.

This structure heavily emphasizes the object, which is useful for contrastive meaning.

Placement of Adjectives and Adverbs

Adjectives Usually Precede Nouns

Adjectives typically come before the noun, but they can also follow it without changing the meaning.

ლამაზი სახლი (lamazi sakhli) a beautiful house

სახლი ლამაზია (sakhli lamazia) the house is beautiful

Adverbs Usually Precede the Verb

ბავშვი სწრაფად გარბის (bavshvi sts’rapad garbis) The child runs quickly.

ის კარგად მღერის (is k’argad mgherisi) He/she sings well.

Adverbs can also appear at the beginning of the sentence for emphasis:

სწრაფად ბავშვი გარბის (sts’rapad bavshvi garbis) Quickly, the child runs.

Word Order in Questions

Yes/No Questions

In yes/no questions, the word order remains the same as a statement, but intonation changes. The verb can sometimes move to the front.

ბიჭი კითხულობს წიგნს? (bichi kitkhulobs ts’igns?) Is the boy reading a book?

კითხულობს ბიჭი წიგნს? (kitkhulobs bichi ts’igns?) Is he reading the book?

Wh- Questions (Who, What, Where, When, Why, How)

Question words (like ვინ who, რა what, სად where, როდის when, რატომ why, როგორ how) usually appear at the beginning of the sentence.

ვინ კითხულობს წიგნს? (vin kitkhulobs ts’igns?) Who is reading the book?

სად ცხოვრობ? (sad tskhovrob?) Where do you live?

რატომ წავიდა ის? (ratom ts’avida is?) Why did he/she leave?

Word Order with Auxiliary Verbs

When using auxiliary verbs (like in compound tenses), the main verb stays at the end, and the auxiliary follows the subject.

მე მაქვს წაკითხული ეს წიგნი (me makvs ts’akitkhuli es ts’igni) I have read this book.

შენ გექნება ნანახი ფილმი (shen gekneba nanakhi pilmi) You will have seen the movie.

The negative prefix "არ-" (ar-) is always placed before the verb, no matter where the verb is.

მე არ მაქვს წაკითხული ეს წიგნი (me ar makvs ts’akitkhuli es ts’igni) I have not read this book.

Word Order in Commands and Imperatives

In commands, the verb is typically placed at the beginning of the sentence for stronger emphasis.

წადი სახლში! (ts’adi sakhlshi!) Go home!

მომიყევი ამბავი! (momiquevi ambavi!) Tell me the story!

არ დატოვო კარი ღია! (ar datovo kari ghia!) Do not leave the door open!

Word Order in Subordinate Clauses

In subordinate clauses, the main clause remains in SOV order, but the subordinate clause can be flexible.

ვიცი, რომ ის მოდის (vitsi, rom is modis) I know that he/she is coming.

მასწავლებელმა თქვა, რომ გაკვეთილი გაგრძელდება (masts’avlebelma t’qva, rom gakvetili gagrdzeldeba) The teacher said that the lesson will continue.

Word Order in Emphasis and Stylistic Variations

Because case markers identify the subject and object, Georgian allows for significant word order variation to emphasize different parts of the sentence.

For example, in poetic or literary texts, you may see Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) or Verb-Object-Subject (VOS) orders used for stylistic effect.

მოდის გაზაფხული (modis gazapkhuli) Spring is coming. (VSO)

ისევ მღერის ბავშვი (isev mgherisi bavshvi) The child is singing again. (VOS)

Questions are an essential part of any language, and Georgian has a distinct way of forming both yes/no questions and wh- questions (who, what, where, when, why, how, etc.). Unlike English, Georgian does not use auxiliary verbs (such as "do" or "does") to form questions. Instead, intonation, question words, and word order play a crucial role in distinguishing questions from statements.

Yes/No Questions in Georgian

Yes/no questions in Georgian are typically formed in two ways:

Keeping the same word order as a statement and using intonation

Using question particles (rarely used in modern Georgian, but found in older forms of speech)